|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Current classes

Rooms and times RUSSA 1103 RUSSA 1121 RUSSA 1125-101 RUSSA 1131-1132 RUSSA 2203 RUSSA 3300-601 RUSSA 3300-602 RUSSA 3300-603 RUSSA 3303 RUSSA 3305 RUSSA 3309-101 RUSSA 4413 RUSSA 4491-101 RUSSA 6633 Note: for RUSSA 4433/4434, click RUSSA 6633/6634.

On-line course materials

These open in new windows.

Mini-Videos

The Anthrax Diaries The Russian Dictionary Tree Lora's Dialogs Beginning Russian Grammar Alphabet Грамматика для грамотных About WAL WAL Login About COLLT COLLT Login The Human Body Dictionary Russian Verbs Олигарх Водитель для Веры Благословите женщину Папа Коммунальная квартира Интервью из России I Интервью из России II Дети из России На атомной речке Интервью из Швеции

Faculty

Slava Paperno (director) Krystyna Golovakova Raissa Krivitsky Viktoria Tsimberov Richard L. Leed (1929-2011) Lora Paperno (retired)

Russian minor

Courses

Important Cornell links

These open in new windows.

Academic CalendarCritical dates Final exams Building Codes Campus Maps Time and Room Rosters RUSSA In Courses of Study Special Conditions

Outside resources

These open in new windows.

Word usageBilingual word usage Викисловарь Словарь русского языка Morphological Dictionary Dictionary of Synonyms МиниКроссЛексика Словарь Даля Википедия «Кругосвет» БСЭ Moshkov's library Журнальный зал Russia's Bards Медуза/Meduza news, etc. Internet radio AATSEEL Mnemonic keyboard Standard keyboard

Study in Russia

Our illustrious graduates

We are in the News!

These open in new windows.

Our student studiesSiberian tigers Produced by two Cornellians TV shows, films... Web Audio Lab... |

Our illustrious graduates

"This was one of my Russian textbooks I absolutely adored. To be able to watch an iconic Russian movie, and understand it very well, was such an accomplishment that I will forever hold dear to my heart." Alisa M I fell in love with Russian during my last semester of high school. I decided to major in it at Hunter College. I worked at a video store owned by Ukranians, and so after classes, I would go to work and practice what I’d learned. I spoke Russian daily, and became so good at it that people seriously thought I was from Odessa! We would sing Russian songs, eat Russian food and enjoy Russian restaurants where I would captivate everyone with my collection of Russian jokes. In my second year of college, I took a course that used Slava Paperno’s textbook, “Intermediate Russian Twelve Chairs”. This was one of my Russian textbooks I absolutely adored. To be able to watch an iconic Russian movie, and understand it very well, was such an accomplishment that I will forever hold dear to my heart.

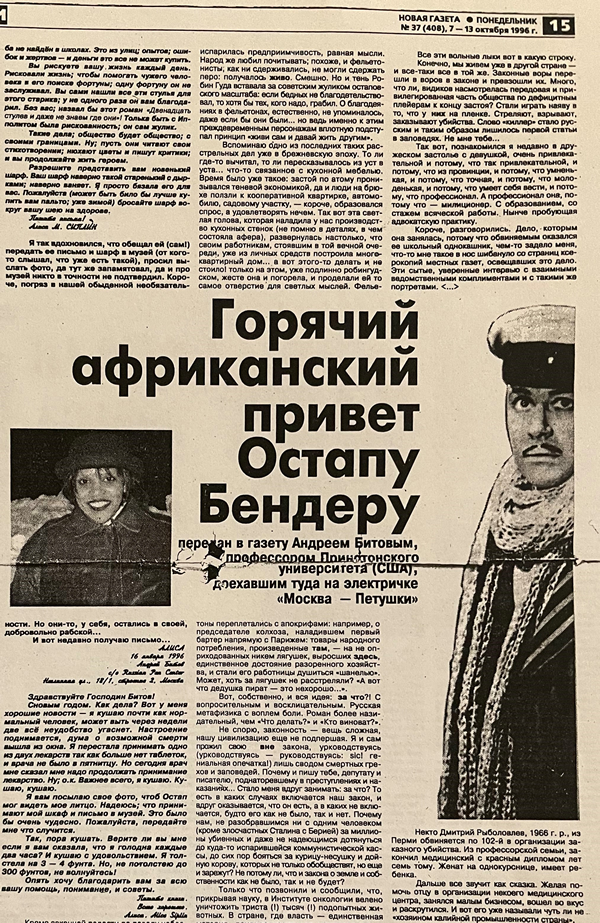

That story is partly about me, written for Novaya Gazeta by Andrei Bitov, who was my college professor in 1996. I wrote a paper for him as a letter to Ostap Bender... In addition to enriching my life, my foreign languages have helped me become a greater asset to my employer. After graduating Hunter, I taught Spanish, Russian and Italian at my old high school as a substitute teacher for a year. I was later hired by INS (now USCIS) to interview applicants for immigration benefits. I was hired at a higher level because of my language skills. I usually use my language skills to conduct interviews of applicants who apply for various immigration benefits, saving me time from finding and using a translator. Back in Brooklyn Citizenship, in the mid- 90’s, word got out that I spoke Russian, so applicants would come to the front counter and demand to be interviewed by "Alisa". The supervisor asked me why they knew my name. She didn't know the Russian community shared info with each other, and since I was semi-famous from my video store days, people recognized me or figured out who I was. These days, I just listen in to make sure the translation is accurate, and when it is not, I ask for clarity and I even correct the translator. I also compare translations of documents to their originals, and sometimes my colleagues ask me for assistance in communicating with applicants who do not understand English. Speaking several languages has brought so much joy to my experience at work. Seeing my Russian-, Spanish-, Italian- and French-speaking applicants' reactions - surprise, happiness and relief (especially the Russian speakers!) - has made working for INS/USCIS more fulfilling than it ever could have been without it. My language skills have led me to work more efficiently and effectively. And happily.

My Master's degree has given me more credibility and looks good on my resume. It shows that I made a commitment to the Russian language at a higher level. And it is definitely a conversation starter. I wanted to learn as much as I could about Russian, so taking graduate classes was strictly to fulfill my need to become more connected with the language. I love Russian. It is a beautiful, strong, rich language. I wish I got my PhD in language acquisition with a concentration in Russian at Bryn Mawr College, but when I was ready to apply, they stopped offering the program. Жулики! My plan was to retire from the government, and teach Russian at a college or university. I may do that anyway, especially since virtual classes may be an option for a while. I’d better start studying!.. And I did! Thanks to Zoom, I finally got into a Cornell classroom in 2021...

~Alisa '21

"I’ve traveled to the UAE and parts of Europe for my current role, where my ability to read and write in Russian has been incredibly useful. My greatest success, however, is outside of the workplace. My husband and I have two beautiful children, a son (17) and daughter (13), both of whom were spoken to exclusively in Russian from birth." Melanie Rakita I enrolled in introductory Russian during my sophomore year at Cornell’s ILR school and still remember the first day of class with Slava and Lora like it was yesterday, both picking up individual items from a desk and saying “это ручка” or “это газета,” followed by “Меня зовут Лора.” and “Меня зовут Слава.” Having grown up the child of Russian immigrants, they quickly discovered I didn’t belong in the introductory class, and were generous enough to create a smaller, level-appropriate course for students like me. Having never learned to read and write in Russian, I enrolled to better connect with my heritage and found the experience incredibly meaningful. I was enrolled in Russian for two years and the memories of my time in those classes are among my most treasured. I was finally able to read the Russian newspapers my parents brought home from Brighton Beach, more confidently interact with my grandparents, and connect with my future grandmother-in-law (who spoke no English). I had a funny (and terribly embarrassing) story in class with my initial speaking skills and recall Slava being incredibly gracious in helping me understand why my (unintentional) word choice was not appropriate (in fact, it was wholly inappropriate). Fast-forward 22 years since graduation. I married my high school sweetheart (a now-physician who immigrated from Kiev and shared many laughs with me as I completed my Russian translations during college). I’ve used Russian throughout my career, both supporting customers in Moscow and speaking Russian when traveling to Turkey for work. Today, I lead Human Resources for a segment of an aerospace and defense company headquartered in Florida. I’ve traveled to the UAE and parts of Europe for my current role, where my ability to read and write in Russian has been incredibly useful. My greatest success, however, is outside of the workplace. My husband and I have two beautiful children, a son (17) and daughter (13), both of whom were spoken to exclusively in Russian from birth. They are intelligent, bilingual, well-adjusted and embrace their heritage. Nothing gave me greater joy than to review colleges with my son, discuss my time at Cornell, and him expressing a desire to attend (he is applying to study Computer Science and would like to minor in Russian).

Our family traveled to Ukraine in 2018 (I had never been there before, and this was my husband’s first time back since he immigrated), where we were introduced to the beautiful history, culture, and amazing food. Everything was so foreign, yet so incredibly familiar at the same time. We visited with family we had not met in person, spent time at a relative’s dacha outside of Kiev, and visited the Privoz (massive outdoor market) in Odessa where my grandfather worked in a meat store in the 1960’s. Taking Russian at Cornell meant so much to me during this trip as I was able to read and communicate with everyone around me. I felt at ease…and at home. And perhaps most importantly, I was able to visit the small villages my parents grew up in, read the names on headstones of family members (including my great-grandparents), and visit historical sites connected with World War II and the Holocaust. I achieved what I set out to do at Cornell so many years ago – and left with an understanding of who I am and where I came from. Thank you, Slava and Cornell, for that opportunity, for caring and investing in my education – you made a meaningful difference in my life.

~Melanie Rakita (née Sacharny), Class of '99

"I never advise anyone to enter academia because jobs are so scarce, but honestly, I love my career, and I don’t think I would have gone into it without the introduction I received at Cornell." Alexander M. Martin I was already interested in Russian when I arrived at Cornell as a freshman in 1981. The Cold War was still on. I also had a personal connection, because my father took business trips to the Soviet Union and came back telling many stories. Lastly, the language intrigued me—the exotic alphabet, the sound of the language, the folk-music records that my dad brought back. I was hooked once I started taking Russian at Cornell, and especially after I spent the spring of 1984 in Leningrad, where the hospitality of Slava’s family and friends made a lasting impression on me.

That’s me in the gray jacket, at the 1984 May Day parade in Leningrad. I wanted to go into a Soviet-related career. At Cornell, I double-majored in history and Soviet studies, but I thought I didn’t want to be an academic. What career to pursue? I toyed with becoming an intelligence analyst, but opted against it because it would have limited my ability to travel to the Soviet Union. My dad thought I should be an international lawyer, so I considered a joint-degree program in Soviet studies and law. But when I asked a professor who was a great expert in this field, he counseled against it: Young man, he said, the Soviet Union is a command economy where everything is decided by the government, so no one needs a lawyer who knows Soviet law. That was sound advice when he gave it in the fall of 1984. Six months later, Gorbachev came to power, but by the time he started dismantling the command economy, my plans had evolved. I decided to be an academic after all. I enrolled in a political science program at Columbia because I thought it was the subject most relevant to present-day issues, but the discipline was a poor fit for me. So, having tried the alternatives, I cycled back to where I had started at Cornell: history. I did my Ph.D. in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s at the University of Pennsylvania. It was an exciting time to do Russian history, particularly the two semesters that my wife and I spent in Leningrad in 1990-91. The Cold War was winding down, the Soviet Union was opening up to the world, the economy was falling apart (they introduced ration coupons while we were there), and a few months after we came home, the country disintegrated. Revolution Day, November 1990: I’m in front of a Leningrad archive, holding a sign left behind by anti-Gorbachev protesters. It reads, “Democracy Without Discipline is Anarchy.” It’s now in my dining room. I earned my doctorate in history in 1993 and got a tenure-track position at Oglethorpe University, a liberal-arts college in Atlanta, where I was responsible for teaching not only Russian history but all of modern European history as well. I stayed there until 2006, when I took the position at the University of Notre Dame that I continue to hold now. I have taught at two wonderful institutions: a small college and a much larger research university. I have had the freedom to explore my interests in Russian history and also my other passion, European (especially German) history. I have written several books on imperial Russia, two of which have appeared in Russian translation. I have been an editor of a major academic journal (Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian Studies). I have spent sabbaticals with my family in Russia and Germany, and I get to go to conferences in America, Europe, and Russia, and to lead student trips to Russia.

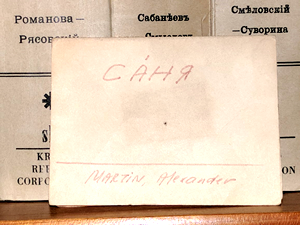

I never advise anyone to enter academia because jobs are so scarce, but honestly, I love my career, and I don’t think I would have gone into it without the introduction I received at Cornell. In Russian class at Cornell, we were all given Russian names and had place cards to put in front of our seats; mine reads “Саня,” and it’s still on my bookshelf. Of all the Russian knickknacks in my home office, it’s my favorite.

Links:

~Alexander M. Martin, Class of 1985

"Although I did not pursue a career involving Russian language, studying Russian and working in the Russian department at Cornell

did have an impact on my life and career in indirect ways, as one thing led to another. "

Heather Behn Hedden I chose Russian as a somewhat “exotic” language yet spoken by a large number of people in an important country in the world. I was fortunate to be able study Russian in high school and participate in a high school trip to the Soviet Union before I came to Cornell in 1983 and continued with Russian classes. I found learning Russian fun, so at Cornell I then took up a second “exotic” language spoken by a large number of people, Arabic.

Despite my interest in Arabic and the Middle East, I remained interested in Russia and the lands inbetween. I was working as a journalist for the Middle East Times in Cairo Egypt 1991-1992, during the time that the Soviet Union collapsed. I made connections with Russians and other former Soviet people in Cairo, and arranged an extended visit to Russia in summer 1992, partially as a freelance journalist, before returning to the U.S.

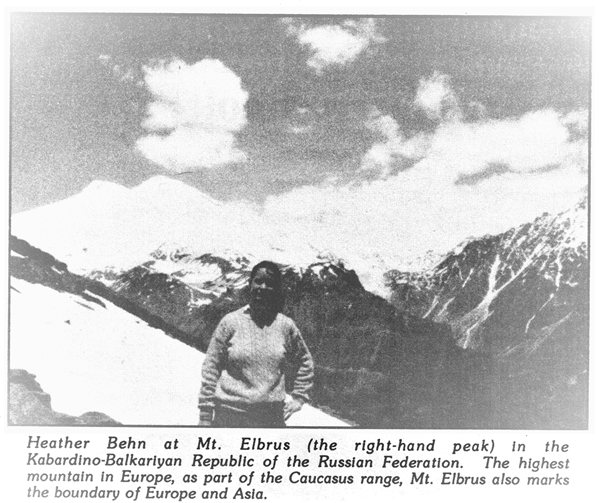

I stayed with Russians in Moscow and St. Petersburg, visited the Crimea, where I wrote an article on an Egyptian joint-venture company,

and for the main part of my stay taught English for 4 weeks in Nalchik, the capital of Kabardino-Balkaria in the North Caucasus.

This is where the Circassian (Черкесы) ethnic group is from, and many Circassians, who are Muslims, had emigrated to what is now Turkey,

Syria and Jordan, when their land was taken over by the Russian Empire from the Ottoman Empire in the late 1800s. I wrote an article for

the Middle East Times about the Circassians I met in Nalchik who were immigrating back from the Middle East.

I also visited the cities of Makhachkala, the capital of the republic of Dagestan in the North Caucasus, and Baku, Azerbaijan, as I had met

people from those cities while at a conference on Islamic studies in Moscow.

Knowledge of multiple languages, including Russian, helped me get my first full-time job after I completed my studies (prior to working for the Middle East Times). I worked as a project coordinator in a translation services agency in Palo Alto, CA. Russian was a common interest with another project coordinator working there (a recent PhD Slavic linguistics graduate of U.C. Berkeley), and two years later he became my husband. Also in the early 1990s, I was a regular contributing writer/editor for Multilingual Computing magazine. My experience with the Russian program at Cornell was not limited to language study. I had a work-study job in the office of Slava and Professor Leed doing Russian data entry to help compile what became the book 5000 Russian Words: With All Their Inflected Forms and wordprocessing in Russian to help create the textbook Intermediate Russian: The Twelve Chairs. My career has since followed an editorial path, as a journalist, freelance writer, and abstractor-indexer. Currently I am employed, perhaps coincidentally, by a major higher education textbook/educational software publisher, Cengage Learning (which does not publish Russian textbooks or software, leaving that to the experts, such as the instructors at Cornell).

I have also pursued teaching and book-writing myself in the field of my profession, which has become taxonomies/thesauri/controlled vocabularies/metadata. My career trajectory was writer > abstractor > indexer > editor of index terms > creator of taxonomies. Between corporate taxonomist jobs, I wrote a practical professional book, The Accidental Taxonomist, published in 2010. Although it is not intended as a textbook, some library science instructors have assigned it for their courses. Meanwhile, I developed and taught a 5-week online course, “Taxonomies & Controlled Vocabularies,” offered through the library science continuing education program of Simmons University. Simmons discontinued its continuing education program in 2016, so I have been offering the course independently through my own business Hedden Information Management, through which I also do some taxonomy consulting. I also do quite a bit of conference speaking, including full-day workshops on how to design and create taxonomies, more recently in Europe, too. I wonder if I will give a conference presentation or workshop on taxonomies in Russia someday.

Links:

~Heather Behn Hedden, Class of 1987

I have fond memories of studying Russian at Cornell with Slava and Lora Paperno. That would have been 1983-7.

The program, and the study of Russian and Russia had a big impact on my life and

led to many great adventures. So thank you for your part in that!

Shawn Dorman I studied Russian at Friends School and visited the USSR in 1983, which sparked my interest in Russian and Soviet studies. During my years in college, I did a summer program in Volgograd. Later I did an internship at the State Department’s Soviet Desk while doing a semester at Cornell in Washington. I graduated in 1987 with a BA in Government and Soviet Studies. The internship led to a job at the State Department and then work in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

I went to grad school, got an MA in Russian Area Studies from Georgetown (working for Professor Murray Feshbach researching Soviet health and environment issues for his book Ecocide in the USSR), taught English in Chanchun, China for 6 months (studying comparative communism), and then joined the Foreign Service and went off to the newly established U.S. Embassy in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan for two years, 1993-5. During that time, I married fellow Cornellian Shawn McKenzie (’86) and he joined me in Bishkek and worked for UNICEF there. After that I served in the political section of the U.S. embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, and then in Washington at the State Operations Center. Then I had a second child and resigned from the Foreign Service and went to work as an editor for the monthly Foreign Service Journal published by the American Foreign Service Association. For AFSA, I put together the book Inside a U.S. Embassy (2003, 2005, 2011) aiming to help build understanding of what the Foreign Service is, who works in an embassy and the role of diplomacy. The book has sold more than 110,000 copies.

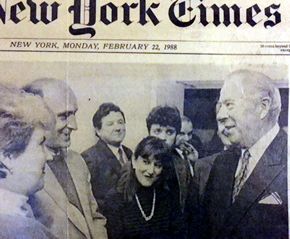

In 2011, in connection with the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Soviet Union, I had the chance to put together a special issue of the Journal, which included a Q&A with President George HW Bush, an article from Secretary of State George Shultz, an article from Ambassador Jack Matlock, and stories from other diplomats who were there during that historic time. I’m now the Editor in Chief for the Foreign Service Journal. We plan another issue with a focus on Russia for spring 2016. I enjoy being connected to the Foreign Service but not needing to move every couple years. I live in Baltimore, and work in Washington. Next week we will bring my daughter, Hannah, for a visit to Cornell... She is a junior in high school.

Links:

~Shawn Dorman, Class of 1987

"The interpreter creates a sort of culvert in her mind through which words and ideas pass unimpeded, like industrial run-off,

from one side of the language barrier to the other. Her mind serves as a temporary dwelling place or

boarding house for a stream of ideas that are not infrequently alien to her, but that never hang around for long.

They mingle in strange ways and ultimately disappear."

from "Articles on Interpretation"

by Laura Esther Wolfson Laura Esther Wolfson

The Papernos had been in America for just one year when I turned up. Lora spoke no English then.

She didn’t need to. Each day she came to class swinging a small basket on her arm.

She brought out the contents, one item at a time. Throughout my college years, the hotel management, agriculture and engineering majors asked, "What will you do with Russian? Work for the United Nations?" I was in it strictly to grow and to connect. The future would take care of itself. My junior year in Leningrad, I witnessed the limbo of refuseniks awaiting exit visas, and visited a communal apartment where I was served homemade raspberry jam from a galvanized bucket. I marveled at the similarity between noon and midnight in Leningrad in June. I read and reread Blok on the color red, sunsets and, by extension, Russian history, and Pushkin on love that is over, but not really. Also, I attended Russian classes at the university. Apparently I progressed, for, back at Cornell, I enrolled in a course on War and Peace. Seeing vibrant Natasha age into a hausfrau engrossed in diapers was bitterly disappointing. During the very last class, our professor insisted that home and family were woman’s highest calling. Several of us ended the semester weeping in the restroom, unsure what kind of women we should become. Perestroika was in full swing as graduation approached. A poster of St. Basil’s Cathedral appeared in the department: "Travel around the Soviet Union and get paid!" Soon I was doing just that, as a Russian-speaking guide on a touring exhibit called Информатика в жизни США (Information USA). The computers and other equipment on display were dated and not even available for sale in the Soviet Union, but as it swung through Georgia, Uzbekistan and Siberia over the course of nearly a year, the exhibit drew thousands of visitors daily, hungry for contact. It wasn't about the hardware; we guides were besieged with questions about the cost of bread and housing in America, unemployment, civil rights, capitalism, the arms race, our opinions of Reagan and of Stalin. We were showered with gifts; we were interviewed on television; we were handed forbidden manuscripts; we were trailed by the police. My cohort of exhibit guides produced one Foreign Service officer, one historian of Russia, one human rights defender, and two conference interpreters. Next, I accompanied Russian performing artists on tour in the United States. Duties included taking ballerinas to get root canals, buying a jacket for a choreographer’s poodle and interpreting for a conductor from the Bolshoi Theater as he rehearsed American musicians. ("And who told you that you were professional musicians?!" he thundered from the podium.) For fifteen years, I worked freelance: an exhibit coworker helped me break into diplomatic interpreting; a well-timed letter to a university press led to contracts translating works of Soviet history; a fellow translator referred me for the translation of a book on Russian obscenities and gulag slang. I interpreted for Russian defendants in US courts, for visiting film directors, poets, human rights defenders, nuclear engineers and military commanders. Recently, I have come full circle, translating web content for Communal Living in Russia and The Anthrax Diaries, sites offered by Cornell's Russian program under On-line course materials on the left. I appreciated the performative, tightrope aspect of interpreting and the proximity to historical events. As a freelancer, I relished taking the interesting gigs and declining the rest. However, by the early 2000s, the Russia craze was winding down; funding was disappearing; and boothmates of long standing were taking regular jobs. We’d been riding a wave, and now the beach was rising up to meet us. My fellow students got it right: I would work at the United Nations. For just as the freelance opportunities were drying up, I met an interpreter from the United Nations, an organization about which I knew almost nothing, except that it employed lots of linguists. The Organization suffered from a shortage of native English speakers who knew Russian, this interpreter told me, but to qualify, I must take my high-school French to a new level. I studied in Paris and Montreal. I immersed myself in the French press and theatre.

There were applications, tests, interviews, freelance contracts, probationary periods. Soon after I started working at the United Nations, I came down with a chronic lung condition, and the associated shortness of breath ended my run as a simultaneous interpreter. I began again in a new department: applications, tests, interviews, etc. Now I’m on staff, and the antics of the international community in all of their idealism and unbridled hypocrisy are my daily fare. I translate diplomatic correspondence, notes verbales, reports, treaties and entreaties from Russian and French to English on such topics as counter-terrorism, global warming, food security and female genital mutilation. The work is like solving a crossword puzzle while dancing a minuet. On a slow day, I may translate some Spanish (which I learned after I was hired), but only if it is short and easy—very, very easy.

Links:

September 2018 interview (Words Without Borders Daily) This was my last interpreting job: author Ludmila Ulitskaya addressing the PEN World Voices Festival in her mother tongue, with consecutive interpretation into English. May 2012, New York City. Interpreting for Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexievich. In December 2006, I interpreted for New Yorker editor David Remnick and human rights defender Natalia Estemirova at a tribute to the late Anna Politkovskaya. This part of the proceedings starts at the 50-minute point. "Articles on Interpretation" by Laura Esther Wolfson. The books at the links below represent a sampling of the translations I have done over the years. (In some cases, I translated some materials or sections, but not the entire book.) These sites, all hosted by the respective publishers, show various ways that a translator's contribution may be credited, including not at all. Stalin's Secret Pogrom. Edited and with introductions by Joshua Rubenstein and Vladimir P. Naumov. The Soviet World of American Communism. Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes, and Kyrill M. Anderson. The Last Diary of Tsaritsa Alexandra. Introduction by Robert K. Massie. Edited by Vladimir A. Kozlov and Vladimir M. Khrustalev. DERMO! The Real Russian Tolstoy Never Used. Edward Topol.

~Laura Esther Wolfson, Cornell University, Class of 1987

"My mother’s friends’ kids were moving to Manhattan or New Jersey after graduating from college. Some might go as far as the west coast.

I was moving to the other side of the Iron Curtain. She was able to manufacture a slew of excuses as to why this was a bad idea for her baby."

from How Not to Become a Spy

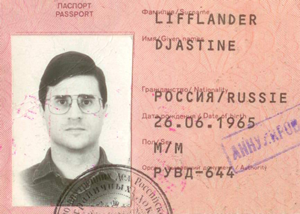

by Justin Lifflander Justin Lifflander: Bicardiohyperclaritinosis is Incurable Embassy driver-mechanic; missile inspector-janitor-sous chef; personal secretary, marketing specialist, salesman, sales manager, business development manager, deputy general manager; entrepreneur with two successful startups created, run and sold; journalist and newspaper editor; executive in an oligarch’s media company… The only profession I actually haven’t had in the twenty seven short years I’ve lived in Russia, despite what everyone believes, is the very one I had in mind when I signed up for Russian 101 that summer in 1983. I am not, and never have been a spy. If you don’t believe me, read my memoir, titled "How Not to Become a Spy," which I hope to find a publisher for. "Another language is another heart," said one of my early mentors when I was still planning on becoming James Bond. He had been Roosevelt’s intelligence advisor and one of the founders of the OSS, though by the time we met he was a wheelchair-bound fossil and well known player in Washington’s very-old-boy network. Stick with the Russian, he said, no matter how daunting. And I was daunted often. Lora Paperno had a memorable way of correcting her advanced students—instead of saying "You made a mistake," she’d simply glare at you and say, "Beginning Russian 101!" to remind you of when you were supposed to have mastered that declension or prefix. The satisfaction of using (or not using) the knowledge gained at Cornell crept up on me slowly over the years. The time I first went into a public cafeteria in Moscow I asked the matronly server to give me two сиски—she smiled forgivingly and placed the hot dogs on my plate. My sins of pronunciation and grammar are still forgiven.

The subtleties of true understanding took time to master. Four years of study and nearly three decades of practical use and social osmosis have brought results. When I began to spot the minor mistranslations while editing the English work of native Russian journalists, I was again reminded of where it all came from. "No, Zhirinovsky’s thinking is not 'inadequate,' it's 'mentally deficient'," I pointed out to the writer, with a sense of intellectual gratification that I was doing some good by bringing the true meaning to our readers. I had gotten the editor job not because of some credential, but because I had demonstrated passion for the two languages—a passion that resides in both my hearts.

Links: «Как не стать шпионом. О ракетах, любви и коте Кузе, заслуживающем доверия.». Москва: Издательство «Весь Мир». 320 стр.

~Justin E. Lifflander, Class of 1987

I was ill at ease in the academic world. I got a job on a boat. And by the time I finished grad. school, I had a plan:

I would join the National Park Service.

Julien Appignani Taking Russian at Cornell is one of the best things I ever did. This is because of Slava and Lora Paperno: my first Russian teachers. I remember stepping into a bright, sunny room in Goldwin Smith Hall to register for class. A small older woman with big eyeglasses and a strong Russian accent invited me to sit down. I said I would like to learn Russian. She smiled and wrote down my name. I was surprised by what happened next. Very politely, she asked: Why did I want to learn Russian? I’d never thought about that. I said I liked the literature, the music: Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff. She smiled again – and signed me up for more credits. It’s many years later, and I’m about to start teaching Russian myself. Let me explain how this happened. After college, I did a fellowship (in Berlin); after my fellowship, I did grad. school (in Chicago). The only good thing to come out of any of this was that I read a lot of Dostoevsky. I even wrote a dissertation on him. But I was ill at ease in the academic world. I got a job on a boat. And by the time I finished grad. school, I had a plan: I would join the National Park Service. I’d always liked literature, and languages, and music; but I’d always liked wildlife, too, and the Park Service suddenly seemed like my chance to get out of the academic world and into this “other” world – whatever that “other” meant. I’ve worked in the Park Service for six years. I lost contact with everyone from college, including my dear teachers. But I thought about them often; and then, one winter’s day, I missed them badly. I remembered my first time meeting Lora; I remembered my first few classes, with Lora and Slava; I remembered how much I loved, absolutely loved, the Twelve Chairs. I thought maybe it wasn’t too late. I wrote Slava an email. He answered within twenty-four hours. I went to Ithaca for a visit. And this, also, is one of the best things I ever did. I work right now at Denali National Park. University of Alaska Fairbanks is 100 miles to the north. After re-reading the Brothers Karamazov recently, on an impulse, I gave the university a call. I introduced myself and asked if they needed any help teaching Russian. I didn’t even know if they had a Russian program. But they do. I start teaching in two weeks – Intermediate Russian: The Twelve Chairs. To my dear teachers, for the warmth that transcends borders, and for the chance to do something as difficult and interesting as not just learning Russian, but trying to teach it, I will always be grateful.

~Julien A. Appignani, Class of 2004

"The arrival of spring to our tiny Russian village of Chukhrai—population nineteen—means that soon the rutted, ice-covered forest road that connects us to the outside world will become passable.

Slowly, the villagers emerge from hybernation... Surrounded on three sides by a strict nature reserve, our village is virtually inaccessible."

from The Storks' Nest: Life and Love in the Russian Countryside

by Laura Lynne Williams Laura Lynne Williams I grew up in Colorado, graduating from Fountain Valley School in 1987. Since earning a degree in International Environmental Policy from Cornell University in 1991, I have worked in the field of environmental conservation in Russia. I first studied Russian in Morrill Hall at Cornell, and travelled to Russia on a language exchange program in 1990. I decided to learn Russian because I was certain that by speaking the language of the world’s other superpower we could progress toward resolving global environmental issues, such as climate change. In 1993, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) invited me to head up its new office in Moscow and help determine conservation priorities for Russia. Together with Russian experts, over the next four years, we raised more than $10 million to create new protected areas and support Russia’s system of strict nature preserves during a time of severe economic crisis. In 1997, I moved to the Bryansk Forest Nature Reserve in western Russia to run the environmental education program and work with local schoolchildren to protect habitat of the endangered black stork. That is where I met my husband, wildlife photographer Igor Shpilenok, who enticed me to a remote village in the countryside, where together we made our home. Then Igor encouraged me to join him on the remote Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East in 2005, one of the world’s greatest wilderness areas. While he photographed bears, salmom, and volcanoes there, I spent the next four years working for WWF and the Wild Salmon Center to help protect a network of pristine rivers with thriving wild salmon runs and viable brown bear populations. I have lived in Russia for over 20 years now, returning once or twice a year to visit my family. In 1999, I spent a "year abroad" to complete a Master’s degree in Conservation Biology at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Igor and I have two sons, Andrei and Makar, who have grown up in Russia and speak fluent Russian and English.

In 2008, Fulcrum Publishing published my memoir "The Storks’ Nest: Life and Love in the Russian Countryside," on my life with Igor in the Bryansk Forest. I also work as a freelance conservation writer, and have contributed articles to National Wildlife, BBC Wildlife, and Russian Life magazines. I recently started a blog in English and Russian on my adventures in Russia.

Links:

~Laura Lynne Williams, Class of 1991

Cori T. Weiner I chose Russian for strange reasons, probably. After seven years of Latin, I knew that not everyone would enjoy learning a language with such a high level of grammatical complexity. At the same time I was particularly interested in anthropology, which inspired me to seek out a non-Western culture. And I’m glad I did, as I feel that studying abroad in a culture vastly different from your own lends you more flexibility in your perception of the world as well as stronger problem-solving skills. I personally became more resourceful and slightly more devious after living in Russia for a while. The experience can also lead to even more travels to that country later on in life, if you are motivated. (It's hard to resist revisiting St. Petersburg!) Interestingly, Russian helped me have understanding for my students when I taught ESL, both in terms of language and culture. I generally did not speak any of my students’ languages—Korean, Japanese, Arabic, Spanish, but I could relate to many of the stories and opinions I heard. I also feel that my teaching style is largely based on how Russians acted towards me when I was a guest in their house—accommodating, understanding and attentive. In terms of career goals, my master plan was to get the appropriate degree so that I could go on to find a job in academia in Russian. But my backup was always to get a TESOL certificate and take relevant coursework because I knew the job market in Slavic was not promising. I encountered countless unnecessary obstacles along the way, and unfortunately, my plans for my education didn’t work out.

My overall plan, however, ultimately did work out to some degree: I lived in Boston for many years teaching ESL (which I ended up really enjoying!) until I got a job teaching Russian. And the upside was that I got to experience a vast range of odds-and-ends jobs along the way: translating for Russian orphans being adopted in the U.S., interpreting for street-style dancers visiting Russia, facilitating the green card process for immigrants, working on a sociology project also involving immigrants, and even teaching at a Russian-speaking preschool. Presently, I'm learning to cook dishes I've never even tasted from regions like Dagestan, Georgia, Armenia and some other -stans. With the help of YouTube cooking tutorials and my faraway conversation partners, I'm determined to further flesh out my Russian profile!

~Cori T. Weiner

If it weren’t for Russian, I would not have the amazing life I have now.

And were it not for Slava and Lora Paperno, and the inimitable Dick Leed, I would not be the teacher I am today.

Cynthia A. Ruder I had superb instruction in Russian language at Cornell while working toward my Ph.D. We conversed in Russian, wrote essays, translated all manner of texts, and through each exercise the teachers guided us with enthusiasm, energy and support. Indeed I’ll never forget a couple of my compositions (we were permitted to write about whatever we wanted in whatever style we wanted) about mundane activities like making soup or washing my clothes. I wrote about the carrots standing up in my soup pot or my jeans standing up in the washing machine—I had used стоит\стоят rather than лежит\лежат. Yet precisely because linguistic experimentation was allowed and because the teachers corrected each essay with care, I learned the correct way to say oh-so-many things. Or there was the time when the teacher wanted us to retell, in Russian of course, a news report to which we had listened. When it was my turn, I—totally by accident I assure you—repeated Slava's question in order to give myself time to think. Well he was delighted because it turns out that is a fabulous rhetorical technique when you don’t know what you want to say or how to say it. Or the many times we were induced us to "talk around" something if we didn’t know the precise word or phrase. I cannot tell you how often I have used these strategies when speaking Russian or teaching others to speak Russian.

Even now, as a tenured professor of Russian Studies at the University of Kentucky, I use those strategies, so I’m very glad that I studied Russian at Cornell. And my Russian husband is glad, as is my Russian mother-in-law! Throughout my career, from teaching all levels of Russian to conducting research in Russian archives and libraries, from conferring with Russian colleagues to appearing as a guest expert in a film shown on the History Channel, this devotion to and love of Russian that has sustained me all these years is largely thanks to the appreciation of the Russian language I cultivated at Cornell. I owe my success and happiness to Russian—the language, the people, the country, the culture, as well as to the instructors who helped me achieve my success. Take Russian! It is a fascinating, fabulous language that opens up a world of opportunity that you might never have thought existed. You don’t have to plan for a career in academia as I did, although that is an option. People who know Russian are in demand in the private and government sectors, and in a variety of careers from journalism and law to engineering and medicine. It is an opportunity that is NOT to be missed. Давайте!

~Cynthia A. Ruder

Russian language at Cornell and my experiences abroad have deeply informed my scholarly research

by expanding my imagination. I think that is useful in any pursuit.

Chris Muenzen What I remember most vividly about the Russian language program at Cornell was the film-based instruction. I always enjoyed watching the movies and learning the dialogues, doing my best to ape the actors' styles of speech and pronunciation. I also remember that we would act out the dialogues and scenes in class, which I enjoyed very much. When I arrived in Russia for the first time after I graduated, I felt as if I was in a film, seeing sights and meeting people the likes of which I had only ever seen on screen. History particularly interested me as an undergraduate, and so I conducted an oral histories project during my Fulbright year. The memorialization of the war really stood out to me. I interviewed a number of veterans, recalling their experiences and tales as soldiers, workers, and nurses. I documented the many shrines, placards, banners, posters, and conversational references to the war. And I spoke with many others to discover what the history of the war meant to them. My interest in history has led me to my current (2015) PhD studies in modern Russian history at the University of Pennsylvania. I am excited to perform my dissertation research this year in Kyiv, Ukraine on pre-Revolutionary consumerism and identity, a topic that will speak to both Ukrainian and Russian history. Perhaps learning a foreign language is like learning how to act, but I am no expert. Nonetheless, Russian language at Cornell and my experiences abroad have deeply informed my scholarly research by expanding my imagination. I think that is useful in any pursuit.

~Chris Muenzen, Class of 2009

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dept. of Comparative Literature

•

Russian Language Program

•

240 Goldwin Smith Hall

•

Cornell University

•

Ithaca, NY 14853-4701, USA

tel. 607/255-4155 • fax 607/255-8177 • email slava.paperno@cornell.edu |

|

_600x393.png)

_600x369.png)